George was born in Charlottetown on June 25, 1872. Life for most was hard at the time, but if you were black, it could be downright miserable. As a young teen, George had no plans to stick around, and as soon as opportunity presented itself, he left to start a new life in America.

Life was no easier at first. He lived as a hobo doing odd jobs where he could, before arriving in Boston in 1890, where he began working on the Hub City’s waterfront, loading and unloading cargo and looking after storage. It was hard, physical work, but it helped develop the incredible physique that was to serve the 150-pound Byers so well in his later career.

A young sportsman convinced George that he had the makings of a wrestler, and he entered a few bouts, successfully winning a few trophies and pocket watches. It was then that he met George Godfrey, another transplanted black islander who made his home in Boston, and he began to learn the finer rudiments of prizefighting.

Godfrey was a qualified teacher – he fought many of the best heavyweights of the era, and he took a liking to the young Byers. After keeping Byers solely as a student for two years, Godfrey brought him out as a professional fighter.

Byers career began in 1895, and effectively ended in 1904. During that time he fought well over 125 prizefights, many of which lasted 10, 15, or even 20 rounds, participants engaging in often brutal encounters with skin tight 2 to 4 ounce leather gloves which brushed and cut a man’s rib section every time they landed.

Fighting as often as two or three times a month, Byers punched it out with the best of them, including some of the greatest prize fighters the professional game had to offer. In 1897 George knocked out Harry Peppers of California to win the Coloured Middleweight Title, and the following year, although weighing no more than 158 pounds, he won the Coloured Heavyweight Championship in 20 rounds against the tough Frankie Childs.

In Byers’ first four years of competition he never lost a scrap, and in 1899 he was publicly calling out the World Middleweight Champion, Tommy Ryan, to put his title on the line.

Ryan, however, as was the fashion of the time, was not going to give up his title to a black man, and he draw the infamous “colour line”, refusing to meet Byers, denying him a much coveted shot at the championship.

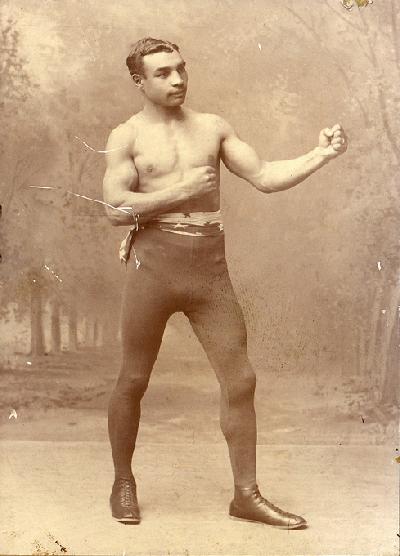

In his time, George was a tremendous fighter – smart, and very clever. “Not for him a cauliflower ear or dented sneezer,”observed Wilf McCluskey in his Ring Ramblings column of 1975. He was the original “pretty boxer” long before Cassius Clay started making his boasts, and photos of the time show how well George looked after himself in the ring. He never hid, and fought the best of his time – he duked it out with every world champion from welterweight through to heavyweight, from Jack Johnson, Tom Sharkey, Bob Fitzsimmons, and Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, the greatest light-heavyweight of all-time, whom he fought to a 6-round draw in Bangor, Maine, in 1902. His nickname Budge, by all accounts, came from the fact that when he was hit, he hardly moved – he didn’t budge.

Some of his fights were exhibitions, many were all out war – even a few were on the quiet, including a bout in May 1899 against future World Welterweight champion Joe Wolcott, a private affair held at George Godfrey’s gym in front of a select few spectators and wagered on heavily. Byers forced the future champion to surrender after four bloody and brutal rounds, though he refused to talk about it in years to come.

With no prospect of a title fight because of his colour, Byers soldiered on until 1904, when he hung up the gloves. Upon retirement he turned to training fighters, and for a short period he was head trainer at the Atlas Athletic Club, and then the Criterion Club.

His greatest pupil was Nova Scotia’s Sam Langford, considered by many to be one of the greatest of all time. According to Langford they met when Byers saved Sam from an angry mob one day. From that pont on they became great friends, Langford crediting Byers with teaching him everything he knew about the finer points of boxing.

For over a decade the two worked together, George acting as trainer, sparring partner and close friend, traveling the globe and seeing parts of the world that many people – especially those of the working class – did not have the opportunity to see. Byers’ association with Sam also afforded him the privilege of being filmed – the only footage of George Byers in existence is that of him training with Langford in France in 1911, and entering the ring with Sam at Los Angeles in 1910.

After Sam and George went their separate ways, Byers settled in Boston, where he continued to train fighters and work at local gyms as a boxing teacher. He took a job on the B and M railroad for nearly 20 years, before he died in Boston City Hospital, either of pneumonia or a heart attack depending on conflicting reports, in 1937.

George’s pedigree as a fighter, and a trainer, was first class. He was, for many years, considered one of the best middleweights in the business, and it was common knowledge that only his color, and not his skill or character, prevented him from gaining an opportunity to demonstrate his championship wares.

George Byers – boxer, trainer, teacher – and Hall of Famer.

As a footnote, it was announced that George was to be inducted in 2008 to the Black Ice Hockey and Sports Hall of Fame in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.

Updated: September 2007

Updated: January 2022

File Contains: Induction package, includes some cuttings, photos, essay by Kevin Smith; CD with CBC radio profile; article by Wilf McCluskey