To a boy participating in the relatively unstructured sports that were played on Prince Edward Island during the summer of 1896, the revival of the Olympic Games in Athens, Greece during that summer was likely of little interest. For Bill Halpenny (pronounced Hay-penny), age 14, that summer was probably a series of long days filled with the enjoyment of playing rugby, some track and field activity, perhaps baseball, and more likely than not, fishing and cycling. But within eight years he would be the first Islander to participate in the Olympic Games, and in 1912 he became the first who has been there twice.

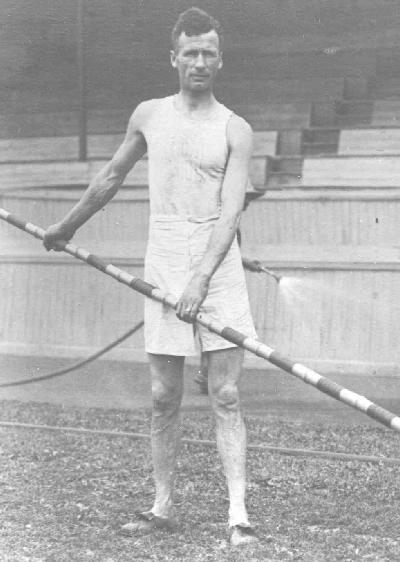

Halpenny’s track and field interest soon encompassed the high jump; the broad jump; the hop, step and jump; the hurdles; and the pole vault. It was in the pole vault, considered the most difficult of them all, that he was to excel. Previous to Halpenny, the only Island athletes to achieve success in vaulting were James MacEachern, later to become an active member of the Abegweit Club, and Marcus Henderson.

Bill Halpenny made a spectacular entrance as a member of the Abegweit Amateur Athletic Association’s track and field team in 1901 by breaking the Maritime pole vault record of 10 feet, 1 inch in his first competition at Charlottetown on August 30. Two of his greatest attributes were already evident: he loved to compete, doing so at every opportunity, and he was consistently able to give his best performances when the challenge was greatest.

The expectations raised by Halpenny’s record-breaking performance during his first competition were quickly met and exceeded. At a series of regional meets during the next three years, he broke his own Maritime pole vault record, established a new Canadian indoor record at a meet in the Hillsborough Rink in Charlottetown, and broke the Canadian outdoor record in a spectacular jump of 11 feet, 5 inches at Summerisde in July of 1904. So impressive was his performance before three thousand spectators at the Summerside Driving Park that on the following day the executive of the Abegweit Club entered him in the Olympics at St. Louis, Missouri. Within three years of Halpenny’s first competitive jump in Charlottetown, the “Boy Wonder” (as he was dubbed by the local press) was on his way to the Olympic Games.

1904 Olympics

The 1904 Olympics were fraught with controversy and uncertainty. Both New York and St. Louis had aggressively sought to host the Games. Because the International Olympic Committee was reluctant to stage the Games in conjunction with the St. Louis World’s Fair, their approval to St. Louis emerged only months before the Games were due to begin. This made it difficult for most countries to prepare teams and as a result the St. Louis Olympics were little more than a North American championship.

Halpenny’s performance in St. Louis was commendable in view of the misfortune he encountered. His pole, shipped by rail, didn’t arrive in time for the competition, and he had to borrow one several inches shorter. In spite of the difficult adjustment this necessitated to his technique, he jumped 11 feet and finished fourth in both the Olympic Games and the Handicap Meet staged in connection with the World’s Fair. The Olympic gold medal was won with a jump of 11 feet, 6 inches by Charles Dvorak of the U.S.A., only one inch higher than the Canadian record established by Halpenny at Summerside two months earlier. On their return to Charlottetown, Halpenny and his entourage of Abegweit executives were given a rousing welcome. The Morning Guardian stated:

A monster crowd with torches and the League of the Cross

Band greeted Wm. Halpenny, L.B. McMillan, Jas Darke and

R. Nicholson at the station last night on return from St. Louis.

The procession marched to the Labor Hall, Kent St., where

speeches were given by the returning ones.

L.B. MacMillan expressed the opinion that Halpenny would have won the gold medal had his pole arrived in St. Louis.

Move to Montreal

Halpenny’s contact with the Montreal AAA and several of its athletes, notably Frank Lukeman, the Club’s outstanding sprinter, was of greater consequence than competing in the 1904 Olympics. Lukeman and Halpenny became close friends during the ensuing years, and it was evident that their friendship and athletic aspirations were mutually influential and supportive. Lukeman made several appearances at the Charlottetown AAA grounds during the summer of 1905 and Halpenny in turn visited Montreal. The result was that Bill Halpenny left the Abegweit Club in Charlottetown to wear the Winged Wheel of the Montreal AAA — then the most prestigious and widely-recognized athletic symbol in Canada.

While the Abegweit Club was well organized and maintained an excellent outdoor athletic facility, Montreal offered the young vaulter better coaching and competition. In the Maritimes Halpenny was clearly in a class by himself in the pole vault, and while he would eventually achieve the same distinction in Montreal, the greater competitive opportunities offered in the latter pushed him to greater achievements.

However, Halpenny found the transition to Montreal and its leading athletic association difficult, and it was a year before he was listed as a member of the MAAA track and field team, and then it was as a broad jumper. Problems were evident when both Lukeman and Halpenny left the MAAA to join its smaller rival, St. Patrick’s AAA. But this defection was short-lived. By late summer the pair again wore the Winged Wheel, and in the next decade Halpenny and Lukeman were the MAAA’s most prominent track and field athletes.

Halpenny’s potential was soon recognized by a comment in the Montreal Star that he “shows rare promise of becoming a great athlete” (Sept. 6, 1906).

A year later, Halpenny “made a splendid showing” as a member of the Montreal AAA team at the U.S. Championship in Norfolk, Virginia, finishing in the top four in both Junior and Senior pole vault events. Several weeks later, Halpenny “soared like a bird” at the Canadian Championship in Montreal. He established a new Canadian record of 11 feet, 5 1/2 inches, defeating A.G. Grant of the New York AC and Harry Harley, his former teammate from the Abegweit Club.

Pre-Olympic Defeat

Canadian trials for the 1908 London Olympics were held in early June, which meant that the athletes were forced to train in adverse conditions. Halpenny dominated the Quebec provincial trials on May 30 in windy and wet weather; besides winning the pole vault, he placed second in the hurdles; the running broad jump; the running high jump; and the hop, step and jump. However, Halpenny’s versatility apparently was a disadvantage at the National Trials a week later. E.B. Archibald of Toronto, competing only in the pole vault, won the event with a new Canadian record of 12 feet, 5 inches. In London, Archibald won the bronze medal with a jump of 11 feet, 9 inches.

Excellence Achieved

Halpenny quickly turned h

is disappointment into action; reassessing his athletic goals, he decided to concentrate on vaulting. To vindicate his Olympic trials setback, Halpenny won a series of victories that included every major North American event in his specialty during the following year. At Travers Island, New York, in September, he won the U.S. National Championship with a jump of 11 feet, 9 inches (the bronze medal height at the Olympics). At the Canadian Championship in Montreal the next summer, he re-established his Canadian supremacy, and in October 1909, he set a new U.S. AAU indoor record of 11 feet, 6 inches at New York’s Madison Square Garden. Second was H.S. Badcock of the New York Athletic Club, an opponent with whom Halpenny would develop a keen rivalry.

The Montreal AAA recognized Halpenny with a special gold medal presented at its December meeting, “to commemorate the new indoor record of 11 feet, 6 inches he made in the pole vault event at the AAAU meet in Madison Square Gardens” (Montreal Star, December 18, 1909). Only two other MAAA athletes had previously been so honoured for international achievement.

Perhaps the most dramatic illustration of Halpenny’s versatility occurred during the summer of 1910, when he won the MAAA gold medal for the summer competition in the Club’s weekly handicap events. By late August, Halpenny was leading the aggregate total by two points over his friend and rival Frank Lukeman and needed points in the 56-pound weight throw and running broad jump. With the benefit of a 6 foot, 11 1/2 inch allowance in the weight throw he placed second, and in the running broad jump he out-jumped Lukeman with one of the best jumps of his career, 23 feet 3 1/2 inches.

The close friendship that existed between Halpenny and Lukeman was disrupted shortly afterwards when Lukeman announced his intention to move to Ottawa to work in that city and compete for the Ottawa AAC. Lukeman was enticed by an attractive job offer, combined with his periodic disagreement with MAAA officials. There was no fanfare for his departure, only a notation in the Montreal Star that Bill Halpenny and several teammates were at the train station to see Lukeman off to Ottawa.

At the Canadian Championship, just two days after Lukeman announced his decision to move to Ottawa, Halpenny did not vault to expectations and lost his Canadian title to Alex Cameron of the Toronto Central YMCA. Cameron displayed excellent technique in winning with a jump of 11 feet, 9 inches. Halpenny and Lukeman were soon reunited at the U.S. Indoor Championship at Madison Square Garden, where they were the only Canadian entries. Both athletes were in winning form, with Lukeman winning the 150-yard sprint in the fast time of 14.5 seconds, and Halpenny successfully defending his title in the pole vault for height, and placing second in the pole vault for distance.

Vaulters from the Toronto Central Y gave Halpenny some of his toughest competition. At the 1908 Olympic trials E.B. Archibald frustrated him, and at the 1910 Canadian Championship Alex Cameron won his title. A year later at the Canadian meet, Halpenny defeated Cameron with a jump of 12 feet, 2 inches to regain the title; he also “missed by a fraction” a world’s record of 13 feet, 3 inches: “Halpenny made three tries for the world record and would have succeeded in his last effort had it not been for the loose end of the number card on his back which caught the cross-bar and threw it down” (Montreal Star, September 25, 1911).

Since his defeat at the 1908 Olympic trials, Halpenny had vindicated himself to a remarkable degree. Awaiting the 1912 trials he could reflect on many achievements, including Canadian and U.S. outdoor pole vault championships, and a U.S. indoor record. But another trip to the Olympics still had to be earned on the day of the national trials. Halpenny, however, rose to the challenge, defeating his old adversary Alex Cameron. At the age of 30, and with over a decade of international competition behind him, Bill Halpenny was about to represent Canada at the Stockholm Olympics.

1912 Olympics

The Stockholm Olympics remain a landmark as the Games that brought to fruition the spirit of the movement as envisaged by Baron De Coubertin, who called them “an enchantment.” Nearly four thousand competitors from 28 countries attended, including 24 pole vaulters. After several hours the vaulters were reduced to six, including Halpenny. The crossbar was now beyond the Olympic record as Halpenny raced down the runway and soared over the bar. He had set a new Olympic record but misfortune struck — landing off-balance he “fell so heavily on his breast” that serious chest and rib injuries forced him to withdraw. The competition was eventually won by Badcock, setting a record of 12 feet, 11 1/2 inches.

However, his injury pointed out the inadequacies of the landing pit to cushion a fall from 13 feet, and the International Olympic Committee acknowledged his misfortune by awarding Halpenny a special Olympic bronze medal. The only precedent for such an award was in 1908 when a similar medal was presented to Dorando Pietri of Italy for his determination to finish the marathon. (Pietri had finished first, but was disqualified because officials had assisted the exhausted and distracted runner.)

Pre-War Achievements

Halpenny recovered from his injuries in time to contest the Canadian track and field championship in Montreal on September 28. Here he vanquished the Olympic record-holder, H.S. Badcock, before a large crowd at the MAAA Grounds. For the moment, he was recognized as the outstanding pole vaulter in the world. He repeated as Canadian champion the next year in Vancouver, but the 1914 meet, due to be hosted by the Abegweit Club in Charlottetown, was cancelled after war was declared. This was a great disappointment for Halpenny and his hometown fans, since, while his exploits were well known locally, the athlete had not vaulted in Charlottetown since he had left for his first Olympics 10 years earlier.

Return to the Abegweits

Following the War, Halpenny accepted the invitation of the executive of the Abegweit Club to return to Charlottetown as coach of its track and field team. The appointment had an immediate impact as young, aspiring athletes trained under Halpenny’s direction. The CAAA Grounds, virtually abandoned during the War, were again the scene of a vigorous athletic program.

Halpenny’s first success as an Abegweit coach was achieved in September 1921, when the team won the Maritime Championship at Saint John. The following September, the team again won the Maritime title in Halifax, an occasion where Halpenny took on his last great challenge with the vaulting pole. Now 40 and out of competitive jumping for several years, he felt the urge to jump one last time to regain the Maritime record he had held for 19 years, but which was now held by Len McDonald of Pictou (11 feet, 1 inch). Performing before over three thousand spectators and a group of his proteges that included Phil MacDonald (who became a member of the 1924 Canadian Olympic Team), Barney Francis (national champion in 100-yard dash and broad jump), Halpenny raced down the runway and cleared the bar for a new Maritime record:

. . . making the most spectacular vault ever seen in Halifax … and the reception he was accorded when Announcer J.D. Vair shouted, “Halpenny clears at 11 feet, 4 1/2 inches” was fit for a king (Halifax Herald. September 8, 1922).

When the team returned to Charlottetown, Bill Halpenny and “Our Boys” were given a rousing welcome which included speeches from Lt. Governor Heartz, Mayor Jenkins, and President Sammy Doyle of the Abegweit Club.

Following his success as track and field coach with the Abegweits, Halpenny accepted the position of Physical Director at the League of the Cross Gymnasium, where he developed a successful program in gymnastics, basketball, volleyball and physical exercise.

In June 1924, Halpenny assisted in forming the League of the Cross Athletic Association, which sponsored teams in track and field, baseball and football. The organization was designed to augment the extensive program of the Abegweit AAA and make a substantial contribution to competitive and recreation sport in Charlottetown.

In the most moderate terms, Bill Halpenny’s commitment to athletic excellence was unusual and his accomplishments remarkable. During his athletic career, he became Canada’s most outstanding pole vaulter, reaching the pinnacle of achievement in amateur sport. As Prince Edward Island’s first Olympian, his accomplishment is worthy of emulation.

Bill Halpenny died in Charlottetown on February 10, 1960.

Updated: July 2018

File Contains: Photographs, letters, biography, medals, Bill Halpenny Award, and news clippings.